Calories Matter… Right?

“If you want to lose weight, you must count Calories.” Isn’t that what everyone says? You’ve all heard this before: If you “burn” more Calories than you consume, your weight will reduce, and vice versa. So, weight management, therefore, is Calorie management. And, since fats have a high energy density (Calories/gram), about twice that of the other two macronutrients—proteins and carbohydrates—you should eat as little fat as possible. Makes sense, right? Unfortunately, no, it doesn’t. Here’s why.

To make this explanation simpler, I’ll generalize. The average person needs about 2,000 net Calories per day of energy to power their anabolic (building) reactions. This is provided by catabolic reactions that break down organic compounds in the food we eat to release that energy. Calories are a measure of heat energy, not mass. A calorie is the amount of energy needed to raise one gram of water by one degree Celsius. A food Calorie is 1,000 calories, or a kilocalorie, which is why we capitalize the “C” in this article (some authors don’t make this distinction). But that’s all about energy, not mass.

Every gram of weight that comprises your body entered only one way: through your mouth. Your weight is a measure of how many grams you ingest, digest, and assimilate, minus the amount of weight you lose in urine, feces, and carbon dioxide. You gain weight based on the mass you eat if that exceeds the mass you lose. Feces consist of the food you eat that is not absorbed. Urine is the fluid intake, from both fluids and the water in solid foods, that are absorbed and then excreted. The rest is what becomes “you,” and it’s the change in mass that makes you heavier, lighter, or the same.

This is what most people don’t understand. I think it’s largely because they haven’t thought about it. Since you need to consume those 2,000 Calories for energy, but want to reduce the weight you consume, you should eat the most Calorie-dense foods (fats), not the least (proteins and carbohydrates).

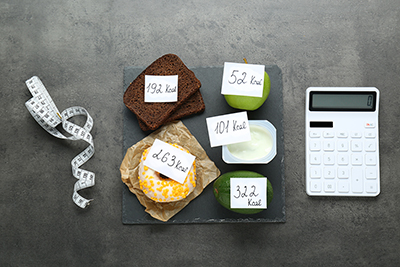

To keep things simple, mathematically, I’ve taken some liberties with the values for energy content and rounded them to the nearest integer and assumed the energy needs of an individual are 2,000 Calories/day. Of course, the latter would increase with body mass, basal metabolic rate, and level of activity. And we all eat a mix of the three macronutrients.

|

Macronutrient |

Energy Content |

Mass Consumed to Meet Energy Needs |

|

Carbohydrates |

4 |

500 g |

|

Proteins |

4 |

500 g |

|

Fats |

9 |

222 g |

* Note that one food Calorie = 1,000 kcal of energy, which is why we capitalize the “C.”

To ingest a mass sufficient to provide 2,000 Calories of energy as carbohydrates or proteins, you’d need to consume 500 grams. But if you consumed only fat, you’d intake only a little over 200 grams because it’s more energy-dense. So, you consume twice as much mass eating carbohydrates and proteins than fats; ergo, it is twice as likely to make you gain weight. But there’s more…

Only carbohydrates cause a significant rise in blood sugar (glucose), which necessitates a rise in insulin, the hormone that removes glucose from the blood and deposits it largely in muscle and fat cells. At low levels of insulin, the glucose is selectively absorbed by muscle cells where it is stored, to a small degree, or burned, if those muscles are active. If not, and the blood sugar and insulin rise—even slightly—our hormones drive glucose to be absorbed by adipose cells and stored as fat. High-carbohydrate diets—as prescribed by our health policymakers—bias our metabolism towards the latter. We gain weight and get fat.

The other simple fact most people don’t know is that, while there are essential proteins (amino acids) and fats (fatty acids)—meaning we must consume them because we can’t fabricate them in our own cells—there are no essential carbohydrates. The only metabolically useful carbohydrate is glucose, and we can manufacture all the glucose we need—about a teaspoon in our blood at any point in time—from noncarbohydrate

The other simple fact most people don’t know is that, while there are essential proteins (amino acids) and fats (fatty acids)—meaning we must consume them because we can’t fabricate them in our own cells—there are no essential carbohydrates. The only metabolically useful carbohydrate is glucose, and we can manufacture all the glucose we need—about a teaspoon in our blood at any point in time—from noncarbohydrate

sources (proteins and glycerol) in a process called gluconeogenesis (literally, “making new glucose”) in our liver and kidneys.

So, it’s not the Calories you consume, it’s the quality of those Calories that matter. Our bodies have evolved on a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet, known today as a ketogenic diet, and when adopted, you will find a new, more natural set-point for your weight, now relatively devoid of carbohydrates. For the average male, that is at least 20–25 pounds lighter, and for the average female, about 10–15 pounds lighter. If you are already obese—and that’s now about ⅓ of the population or more, depending on where you live—it could be much more.

There’s a well-known adage in weight management: “If you’re overweight and you lose that extra weight, whatever you did to lose it, you have to keep doing for the rest of your life.” That’s why Calorie-restricted diets—which are most “diets”—won’t work in the long term. As soon as you go off them, the weight comes back. Plus, by restricting Calories, you are also restricting the micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals) that come with the food you eat, so you are likely malnourished. The other well-known adage is: “Weight management is about 80% diet and 20% exercise.” Stated another way, you can’t outrun your fork. If you have a poor diet, all the exercise in the world won’t have much effect.

There is a healthy, natural, drug-free way to reduce and manage your weight. It is a well-formulated ketogenic diet. And the great news is that you also reduce your likelihood or severity of chronic disease (cancer, cardiovascular disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s) by about 70%. I’ll explain more on that in the Winter issue.

Dr. David G. Harper, PhD

Dr. David G. Harper, PhD

Dr. Harper is an Associate Professor of Kinesiology at the University of the Fraser Valley and was a Visiting Scientist at the BC Cancer Research Centre, Terry Fox Laboratory. He holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia and completed his postdoctoral fellowship in comparative physiology at the University of Cambridge.

biodiet.org

Stores

Stores